Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: A Pivotal Artistic and Personal Relationship

The relationship between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz was a defining partnership in American art, deeply shaping both of their careers and leaving an enduring legacy. Their bond, rooted in both mutual artistic admiration and an intense personal connection, spanned more than two decades, during which they influenced one another profoundly. O'Keeffe, now celebrated as one of the greatest American modernists, and Stieglitz, a pioneering photographer and art promoter, together forged a path that helped to redefine the trajectory of 20th-century American art.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe exhibition, 291 Gallery, 1917 (Georgia O'KeeffeMuseum)

The Early Encounter: A Meeting of Minds and Visions

In 1916, O'Keeffe's artistic journey intersected with Stieglitz's when a mutual acquaintance, Anita Pollitzer, showed him a selection of O'Keeffe's charcoal drawings. At the time, O'Keeffe was relatively unknown, working as an art teacher in Texas. Stieglitz, who was already a well-established figure in the art world and a central figure of the New York avant-garde, was immediately captivated by the raw emotional power and originality of her work. He declared, “Finally, a woman on paper,” recognizing O'Keeffe as a talent that needed to be seen. Without her prior permission, Stieglitz included her works in an exhibition at his famous 291 Gallery in New York. While O’Keeffe was initially startled by this act, it marked the beginning of their profound connection.

Their relationship grew out of a mutual respect for each other’s creativity. O’Keeffe admired Stieglitz’s role as a champion of modern art in America, while Stieglitz was in awe of her artistic originality and the sensuality and abstraction in her works. They began a passionate correspondence, which would evolve into one of the most significant love affairs in art history.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe exhibition, 291 Gallery, 1917 (Georgia O'KeeffeMuseum)

The Romantic and Artistic Union

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz’s relationship moved from admiration to deep affection, with Stieglitz leaving his wife, Emmeline Obermeyer, for O'Keeffe. By 1924, they were married, despite an age difference of 23 years. Their marriage marked the convergence of two strong and independent artistic spirits.

Stieglitz, throughout his career, had played a pivotal role in promoting European modernists like Picasso, Cézanne, and Matisse to American audiences. He was equally passionate about elevating American artists, and O’Keeffe became his primary focus. He helped establish her as one of the leading figures in modern American art, organizing multiple solo exhibitions of her work in New York and promoting her as a central figure of his circle.

Their relationship was also famously documented through Stieglitz’s camera. He photographed O’Keeffe extensively over several decades, producing more than 300 portraits of her. These photographs, ranging from intimate nudes to powerful headshots, portrayed her as a muse, an artist, and a woman of remarkable individuality. These images, particularly the nudes, caused a stir in the art world and added to the mythology surrounding O’Keeffe’s art. Though many critics tried to link O’Keeffe’s art with her personal and sexual life, O’Keeffe herself was often resistant to these interpretations, preferring her art to stand on its own merit.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1918) by Alfred Stieglitz. (Art Institute of Chicago)

Mutual Influence and Diverging Paths

While their artistic careers thrived alongside one another, the dynamic of their relationship was not without complexities. Stieglitz, always the public figure and intellectual, preferred the urban environment of New York City, where he could continue to influence the art scene. O’Keeffe, however, increasingly found herself drawn to the vast landscapes of the American Southwest. The desert landscapes of New Mexico became a major source of inspiration for O’Keeffe’s work from the late 1920s onward. The mountains, bones, and flowers she painted there became synonymous with her artistic identity, reinforcing her reputation as a painter deeply attuned to nature and the American spirit.

As their geographic and emotional distance grew, their relationship became strained. O’Keeffe began spending more time in New Mexico, seeking solitude and a connection to the land, while Stieglitz remained entrenched in the New York art world. Despite the physical separation, the two remained married, and their correspondence and occasional visits kept the connection alive until Stieglitz’s death in 1946.

Georgia O'Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz, 1918 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Legacy of the Partnership

The relationship between O'Keeffe and Stieglitz is often seen as a complex intertwining of love, mentorship, and mutual artistic influence. Stieglitz’s early championing of O’Keeffe’s work undeniably helped launch her career, and his photographs contributed to her growing mythos as an iconic figure in American art. O’Keeffe, for her part, became not only a muse but an artistic equal and, in many ways, surpassed the achievements of Stieglitz, particularly in terms of public recognition in her later years.

Their union represents a quintessential American story of modern art—one where two strong personalities with distinct visions could come together to inspire each other yet ultimately forge their own paths. After Stieglitz’s death, O’Keeffe devoted herself to managing his legacy, ensuring that his contributions to photography and modern art were preserved. Simultaneously, she continued to develop her own work, cementing her position as a pioneering female artist whose bold representations of flowers, skulls, and landscapes became defining images of 20th-century American modernism.

In reflecting on their relationship, it’s clear that while Stieglitz played a critical role in O’Keeffe’s early career, she transcended the role of muse or protégé. She became a pioneering force in her own right, one whose relationship with Stieglitz shaped, but did not define, her artistic legacy.

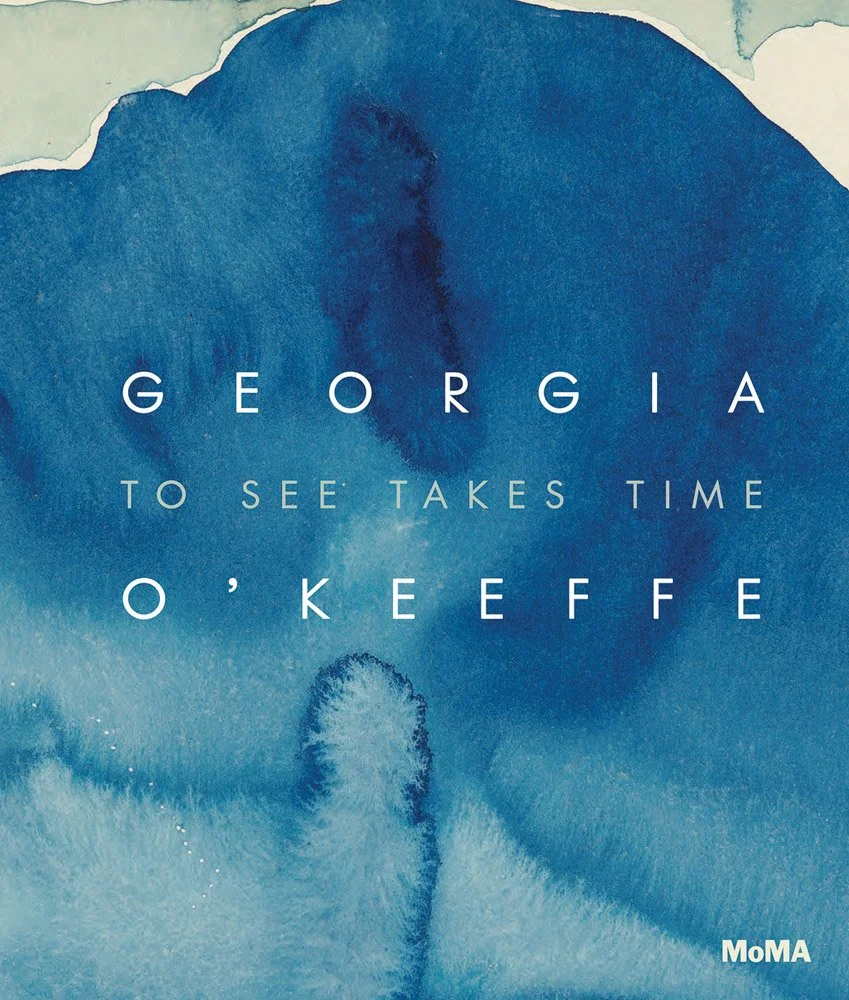

Georgia O'Keeffe: To See Takes Time

A revelatory new volume on the American modernist's lesser-known works on paper, reuniting many serial works for the first time. These drawings, and the majority of O'Keeffe's works in charcoal, watercolor, pastel and graphite, belong to series in which she develops and transforms motifs that lie between observation and abstraction. In the formative years of 1915 to 1918, she made as many works on paper as she would in the next 40 years, producing sequences in watercolor of abstract lines, organic landscapes and nudes, along with charcoal drawings she would group according to the designation "specials."