Robert Colescott: Subverting History with Satire and Color

Robert Colescott (1925–2009) was a master of provocation, using humor, satire, and bold color to challenge racial stereotypes, art historical traditions, and the sanitized narratives of American history. Best known for his vibrant, often chaotic canvases that reimagined Western masterpieces with Black subjects, Colescott forced viewers to confront the absurdity and violence of racial caricatures embedded in American culture. His work straddles the line between discomfort and revelation, beauty and grotesque, past and present.

Despite Colescott’s undeniable influence, many details of his life and career remain overlooked. His experience as a soldier in World War II, his time studying in Egypt, and his early abstract expressionist years are often lost in favor of discussions about his later controversial work. To fully understand Colescott’s impact, we must examine not only his art but also the complexities of the man behind it.

Early Life and the Influence of War

Born in Oakland, California, in 1925, Colescott grew up in a relatively progressive environment, but racism still shaped his early life. His parents were both musicians, and his father also worked as a waiter on the Southern Pacific Railroad—a profession that exposed the young Colescott to a wide array of cultural influences.

During World War II, Colescott was drafted into the U.S. Army and served in a segregated unit in Europe. The experience was a turning point for him. While stationed in France, he encountered modern European art for the first time, particularly the work of Picasso and the surrealists. This exposure, combined with the reality of serving in a racially divided military, planted the seeds for his later critiques of American society.

From Abstract Expressionism to Egypt: A Radical Shift

After the war, Colescott studied at the University of California, Berkeley, where he initially embraced Abstract Expressionism. Like many young artists of the time, he admired painters like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. However, a transformative experience in the 1960s led him to abandon abstraction in favor of figuration.

In 1964, Colescott moved to Egypt to study with the French painter and educator Georges M. Shehata at the American Research Center in Cairo. There, he immersed himself in the rich visual traditions of Egyptian art. The elongated forms, narrative compositions, and bold use of color in ancient Egyptian frescoes had a profound impact on his style. More importantly, his time in Egypt made him see race from a global perspective. He realized that American notions of Black identity were uniquely constructed and historically manipulated. When he returned to the U.S., his work took a radical turn—becoming deeply satirical, political, and unapologetically figurative.

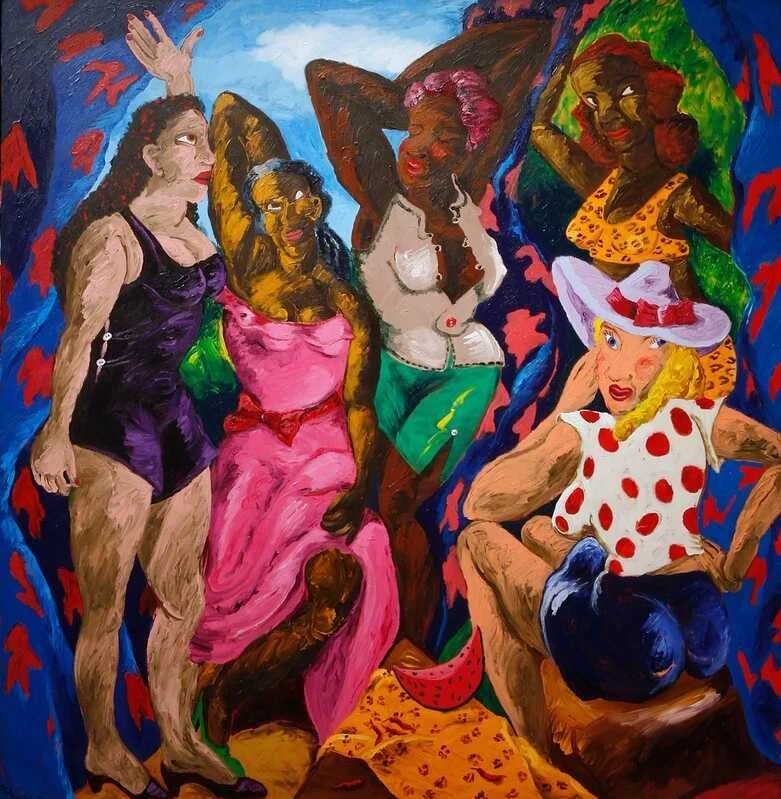

Robert Colescott, Modern Day Miracles, 1988, Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 72 in. (213.4 x 182.9 cm). Rubell Museum

Rewriting Art History with a Brush

Colescott’s most famous works are his reinterpretations of iconic Western paintings, replacing white subjects with Black figures while injecting social and political critique. His 1975 painting George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook is a prime example. Inspired by Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), Colescott replaces the heroic figures with exaggerated Black stereotypes—minstrel-like characters, a jazz musician, a washerwoman, and even a watermelon-wielding soldier. The piece is both a biting critique of racial caricatures in American culture and an assertion of Black agency in historical narratives.

Another major work, Eat Dem Taters (1974), parodies Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885). Instead of depicting a struggling Dutch peasant family, Colescott replaces them with grotesquely smiling Black sharecroppers in a cartoonish, racist stereotype reminiscent of minstrelsy. The painting is often misinterpreted as reinforcing stereotypes, but Colescott’s intent was the opposite—he was exposing their absurdity and highlighting how these images had been used to dehumanize Black people for generations.

Colescott didn’t just appropriate famous paintings; he also inserted himself into art history’s exclusionary canon. In Les Demoiselles d'Alabama: Vestidas (1985), he repurposes Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), replacing the abstracted African masks with exaggerated Black female figures. By doing so, he questions how modernist artists like Picasso borrowed from African aesthetics while ignoring or distorting Black representation in their own societies.

Robert Colescott, George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook, 1975, Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles, © 2021 The Robert H. Colescott Separate Property Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Controversial Humor of Colescott

One of Colescott’s most overlooked qualities is his humor—often crude, sometimes offensive, but always intentional. He understood that humor could be a powerful tool to disarm viewers and force them to engage with difficult topics. His use of satire aligns with the tradition of Black comedians like Richard Pryor and Paul Mooney, who weaponized comedy to reveal racial absurdities.

Yet, Colescott’s humor was sometimes misunderstood, even by fellow Black artists. His use of racial stereotypes led to criticism from those who felt he was reinforcing rather than deconstructing them. Colescott, however, believed in the power of reclaiming imagery. In his words, “You have to go to the negative and drag it out into the light.”

A Late-Career Milestone: Venice Biennale Recognition

In 1997, Colescott made history as the first Black artist to represent the United States with a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale. His selection was a groundbreaking moment, though it was not without controversy. Some critics questioned why a politically charged, confrontational artist was chosen to represent the nation. Others saw it as long-overdue recognition of a trailblazer.

His Biennale works featured his signature mix of satire and social critique, tackling themes of colonialism, race, and power. Yet, despite this global recognition, Colescott remained somewhat underappreciated in mainstream art circles, with his work often dismissed as too provocative or too difficult to classify.

Robert Colescott, Les Demoiselles d’Alabama: Vestidas, 1985. Seattle Art Museum

Legacy and Influence

Colescott’s influence can be seen in the works of contemporary artists like Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, and Mickalene Thomas—artists who challenge historical narratives, use irony to critique racial representation, and reclaim Black agency in visual culture.

Today, Colescott’s works are collected by major institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. Yet, his legacy is still being reassessed. His use of racial stereotypes as a critical tool remains a subject of debate, but his impact on Black representation in American art is undeniable.

Colescott was not simply a painter of provocation; he was a historian with a paintbrush, unearthing the distortions of the past and forcing us to confront them. His ability to mix humor with social critique, abstraction with figuration, and art history with racial politics makes him one of the most complex and important artists of the 20th century.

As more scholars and curators revisit his work, one thing remains clear: Robert Colescott wasn’t just painting history—he was rewriting it.

Please Consider Becoming A Member. As an Independent Publication We Rely Solely on Donations & Memberships.

Become a Member Today